With the red harvest complete, and extended macerations underway, I’m starting to think more concretely about how barrel aging will affect the wine and how we can use this understanding to enhance quality. It goes without saying that barrels are not neutral vessels. Aromatic substances in oak quickly diffuse into wine, and some of these combine with or react with substances in the wine to create new flavors. It’s a bit like using spices while cooking. A little bit can enhance the natural flavor of the ingredients, adding complexity and depth. Too much can hide great ingredients, and faulty ones. Oak also contains tannins that have both beneficial and detrimental effects on wine.

Each of the 40 or so coopers in France have developed their own style that starts with tree selection. The final characteristics of a barrel are related to the species of oak (for example, sessile oak adds depth to fruit flavors), the terroir of the forest where the trees grow (for example, wetter regions tend to grow faster and have looser grain), and the portion of the tree that each stave comes from (for example, staves from the outer portion of the tree tend to have finer grain). Only trees of a certain width will be large enough to make both inner and outer staves from the heartwood, so a cooper that wants to make very fine grain barrels needs to buy larger trees, all else equal. Then each cooper adds its own differentiating touches. Some only cut trees during a waning moon from October to January when the amount of sap is lower than it is at other times. Sap provides nutrients for spoilage microbes and attracts insects, and expansion of sap when it freezes can result in cracks in the wood.

Once the staves are cut, the climate in the mill yard affects the seasoning process. Wet conditions are associated with slower aging and more microbial activity, which can add new and complex flavors. Staves are routinely aged for two years to dry and stabilize the wood, soften the tannins, and reduce or change flavor substances, but in some cases, there is additional benefit to three years of aging. We have seen barrels that have imparted a green sappy taste to wines, the result of poor or inadequate seasoning. Stave seasoning can also be influenced by the position of the pallet in the yard (wood near the outer portion of the yard seasons faster because it is exposed to more wind) and how closely the staves are packed together. Some coopers rotate their stock and have fewer staves per pallet to avoid this variation.

Toasting is another source of significant variation between barrels. Most barrels are exposed to fire to allow the staves to be bent and are then toasted to change the nature and quantity of flavor molecules that are released into the wine. All coopers have their own recipe for this process. Some use higher temperature fires for shorter periods of time while others use lower temperature for longer periods. Some coopers use infrared thermometers to toast to a specific temperature while others add sensory evaluation (aroma and color) to judge when the desired toast level has been achieved. Some turn the barrels over the flame more frequently than others. If you have ever grilled meat on a wood fire, you understand what a difference these variables can make in the final product.

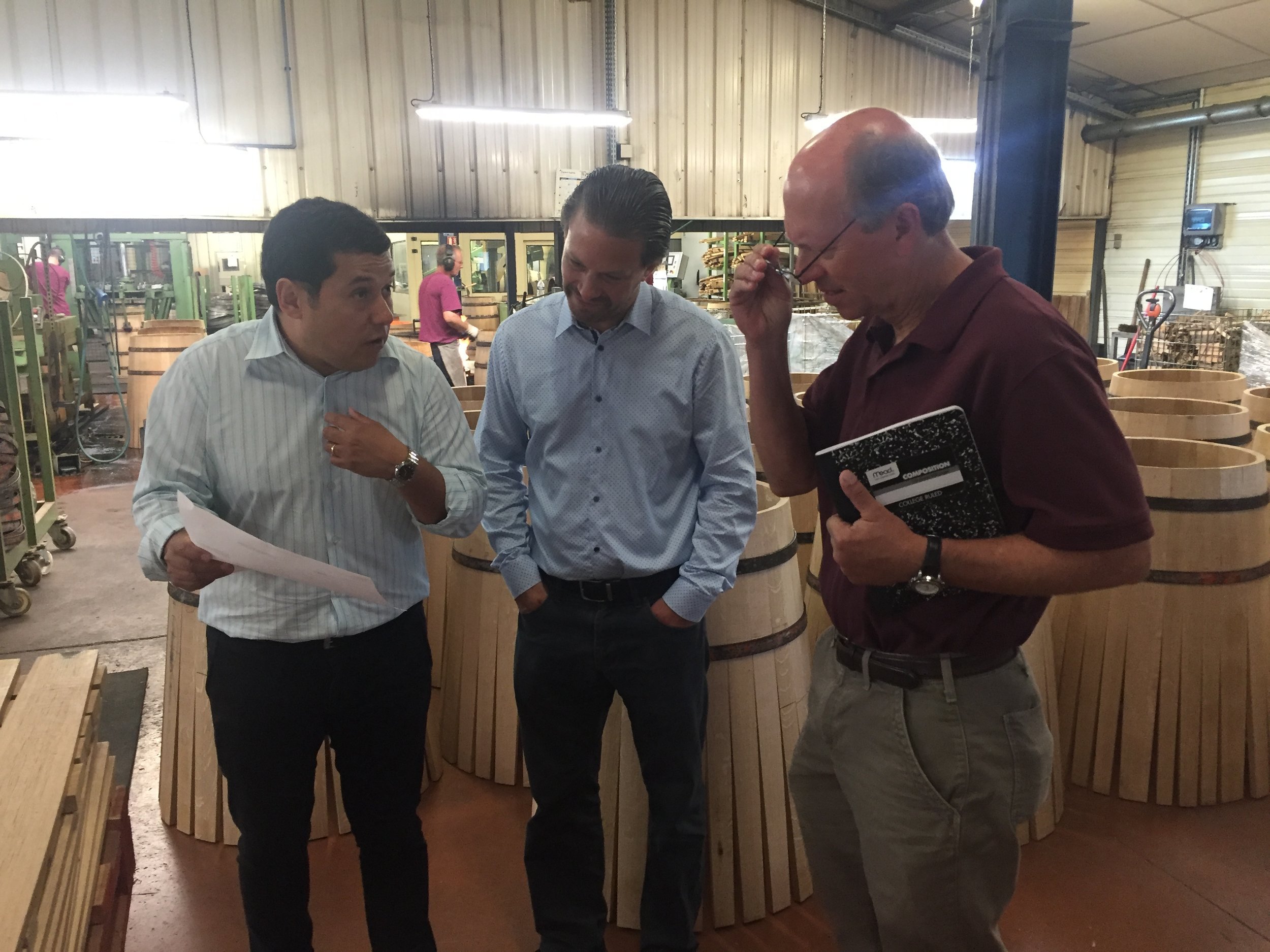

Because of variation in cooper style, it’s often the case that very well-made barrels pair poorly with wine from a single vineyard, or even plot within a vineyard. Many of the best winemakers use an extensive process to evaluate barrels. Several months ago, Polly and I were invited by Eloi Jacob, general manager at Chȃteau Fonplegade, to taste a single lot of 2016 Merlot that had been aged in ten barrels from seven different coopers. We were joined by our consultant Steve Blais, the Fonplegade winemaking team, and representatives from most of cooperages. The tasting was blind to all of those participating, and Eloi had developed a thorough scoring sheet that we used to compare and contrast the aromas and palate of each sample. The differences between the ten samples was stunning.

At Dodon, we also conduct systematic trials of barrels from new coopers to find the right barrels for a wine. Each barrel is tasted and scored for flavor components at least three times in the first year of use. As a result, over the past five years we’ve moved from an even mix of fine and medium grain and toast levels to very fine grains, thin staves, and lower toasts. (Unfortunately, the move to finer grains and lower oak impact also moves us further from the species of oak that grows at Dodon, Quercus alba, so it’s unlikely that we’ll make our own “Dodon” barrels any time soon.) For the 2017 vintage, we purchased from only one of the six coopers we started with five years ago. We’ve instead started working with four smaller coopers who are willing to fine tune the toasts, perhaps adding a minute or two to the standard recipe for a specific situation.

Continuous evaluation and improvement is a very healthy process, one that we embrace fully. We have tasted recent vintages of Dodon wines with most of the coopers that we work with, but to have representatives from all our coopers participate in a single blind evaluation of each other’s barrels would result a much more thorough, critical evaluation. In the end, selecting barrels is a continuous process of systematic trials combined with rigorous evaluative techniques such as the one used by Fonplegade.