We were recently asked for simple definitions of common wine chemistry terms, like brix, acidity and pH. Dodon’s assistant winemaker, Kurtis, took some time to respond. We thought our community might enjoy his answers!

In North America, we measure the sugar content of grapes using °Brix. Brix represents the total soluble solids (SS) in a solution. In wine grapes, these SS are primarily made up of the fermentable sugars glucose and fructose. A typical range of °Brix at harvest is 19-25°, a number that tells a winemaker how much alcohol they should expect after fermentation is complete. So, a wine with 21°Brix could be estimated to yield 11.7%-13% abv depending on the fermentation temperature, the yeast used, and storage conditions.

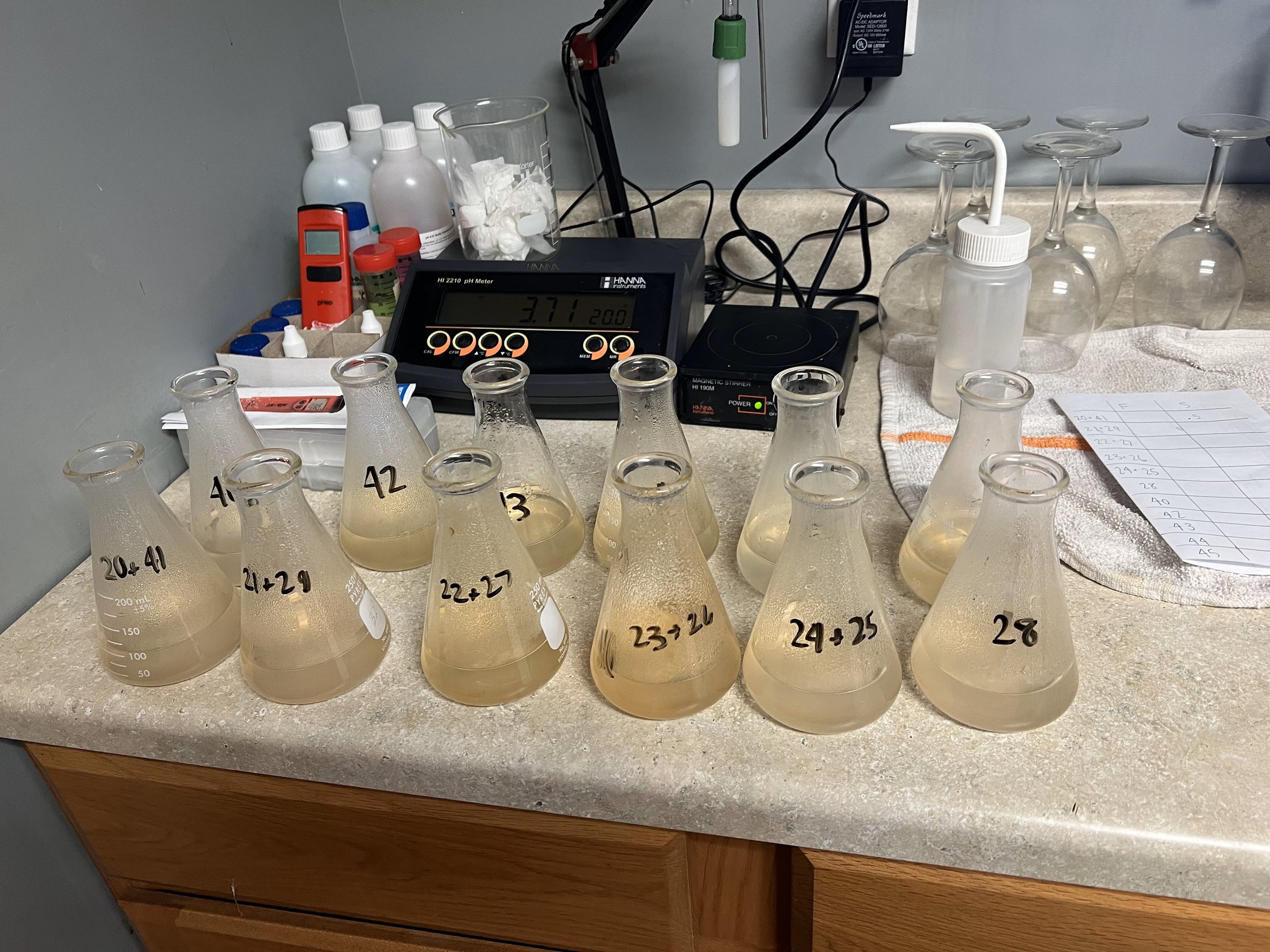

Acidity is arguably what makes the taste of wine unique compared to other alcoholic beverages. Tartaric, malic, and lactic are the chief acids in wine and vary in proportion depending on the farming methods used to grow the fruit, when it was harvested, and how the wine was made. Tartaric acid is the primary acid in grapes and has the most significant influence on taste. Too much tartaric acid can make wine taste sour. Malic acid, the principal acid in apples, is secondary to tartaric but still naturally present in grapes. It tastes sharper than tartaric acid - think green apples. Lactic acid, the acid that lends milk its freshness, is a "softer" acid. It is the product of the conversion of malic acid during malolactic fermentation. We measure the acidity in wines as titratable acidity (TA) in grams per liter (g/L), so a wine with 8g/L TA has more acid and is more acidic than 4g/L.

Wine pH is generally between 3 and 4 on a scale of 0-14, with 0 being the most acidic, 14 the most basic, and 7 neutral. Wine pH measures how many free hydrogen ions (H+) are in an acidic solution. H+ comes from the various acids present in wine, but the absolute amount of H+ depends on how strongly it binds to the underlying salt, sodium tartrate, for example, or other components, such as the tannins, in a wine's solution. A wine's pH partly correlates with the quantity of tartaric, malic, or other acids. For example, two wines could have 7g/L TA but have a pH of 3.3 and 3.5, respectively.

Winemakers are primarily concerned with pH because of the effect on longevity and spoilage. High-pH wines tend to oxidize at a higher rate, giving them a nutty taste, and they are subject to microbial spoilage. High-pH wines may thus require more sulfites.

These three components of wine have a very close relationship to each other and account for most of a wine’s taste. The Brix/sugar content of wine yields ethanol, which masks bitterness, imparts sweetness, creates body, and influences aromatics. A wine with low alcohol would taste thin and watery, whereas high alcohol wine tastes hot and overpowering.

Acidity and the subsequent pH create freshness in wine, preserve aromatics, decrease bitterness, and make wine food-friendly. Wine’s acid levels can accentuate or diminish the other flavors present. Think of it like lemonade without the proper proportion of lemon juice to sugar. If there is not enough lemon juice, the drink tastes too sweet. If there is too much, then it tastes sour. The balance of wine comes from the stylistic choices of alcohol content, acidity, and tannins.

General guidelines for how a region/grape/style can affect these three elements are:

Cooler temperatures retain more acidity in the grapes but provide lower Brix

Warmer temperatures lose more acidity but can develop higher Brix

The varietal grown can considerably impact acidity levels and how early the fruit ripens (thus, how much time they have in the growing season). Petit Manseng has notoriously high acid levels and thus ripens very late in the season.

The winemaker's style and decision of when to pick significantly impacts the varying levels of Brix and acidity. For example, if they pick early or underripe, the grapes could retain a lot of acidity even if grown in a warm climate.

To help demonstrate how these three components of wine are linked, I’ve included two hypothetical examples of a potential grape analysis on opposite spectrums:

Low Brix/ High Acid/ Low pH

Example numbers: 19°Brix, 12g/L TA, 3.10 pH

Cool growing regions allow for these characteristics and are typical of sparkling wines. The high acid is desired for the bright and acidic taste of sparkling wines while the low Brix would yield a lower abv. This is ideal because the secondary fermentation that most sparkling wines go through increases the alcohol slightly.

High Brix/ Low Acid/ High pH

Example numbers: 25°Brix, 4g/L TA, 3.70 pH

A vine can naturally impart enough sugar to reach around 25°Brix; anything past 25° results from dehydration. Most 25°Brix wines can only be achieved in warm and dry climates with a long growing season. The resulting wine would be around 15% abv and likely lack acid. The result can be a bold, powerful wine style that should be consumed relatively soon after bottling.

Growers and winemakers can also influence the balance of sugar and acid present in wine. For example, regenerative agriculture methods like cover crops and animal integration that build soil health have been shown by David Montgomery to increase vitamin C levels, the precursor of tartaric acid, in crops. At Dodon, we have seen a 50% increase in titratable acidity since implementing these techniques. These methods also reduce Brix and, thus, alcohol and are likely to help mitigate the effects of climate change-induced warming.

In the cellar, many Chardonnay makers use a naturally occurring bacterial fermentation to convert malic acid to lactic acid, resulting in a smoother, fuller-bodied, less tart wine.

Kurtis joined the team in January 2023. After graduating from The Culinary Institute of America, he started his career in the restaurant industry in Annapolis. His curiosity about food preservation led him to fermentation and a wine career. Kurtis served as a harvest intern at Dodon in 2020 and 2021 at Antiyal in Chile’s Maipo Valley. After his internship, he moved to The Wine Collective in Baltimore as Assistant Winemaker. Kurtis recently completed the Winemaking Certificate Program at UC Davis and is eager to apply what he has learned to Dodon's vineyard and wines.